This is an independent review of the book ‘Figure it Out: Getting from Information to Understanding’ by Stephen P. Anderson and Karl Fast.

It is part of our series of community member reviews critiquing UX books. Read some of our other reviews or see the full list of recommended books.

The Book

Title: Figure it Out: Getting from Information to Understanding

Authors: Stephen P. Anderson & Karl Fast

Publisher: Two Waves Books (An imprint of Rosenfeld Media)

Price at time of review: Paperback + Ebook bundle USD$32.00; Ebook only USD$13.00 (prices from Rosenfeld Media website)

Book Summary

In this book, Anderson & Fast remind us that information is only understandable in relation to people and their needs. They follow that we must strive to make information understandable, perhaps involving testing “with the intended audience”, evaluating the understandability, and iterating “until it reaches an acceptable level of understanding” (p.13). In the introduction they explicitly pose the question; how might we help others make sense of confusing information?

Based on this, I was expecting a ‘how to’ book to help us present information in a way that aids understanding — to help designers do the heavy lifting of sense-making, and to provide users with understanding and not just information.

This would have been useful given the wide range of industries that need to make information understandable in our modern world — from creators of content to anyone writing a complex privacy policy or ToS agreement. Communicating complex information that needs to be understood by the masses is always important, but especially now amongst the current COVID-19 pandemic. The authors themselves remind us that we, as consumers of information, should expect more — especially when it is coming from experts and professionals. State health and public safety information should be unambiguous.

Instead, Anderson & Fast’s ‘Figure it Out’ is a book about the ways in which we think and how humans understand information. This isn’t to say that I didn’t enjoy it, or that it isn’t a useful book. It is a theory-heavy look at perception that is perhaps suited to more junior (or trained on the job) UX and UI designers who want to learn how users understand and perceive. I make this distinction because any designer coming from a psychology- or Human-Computer Interaction– (HCI) focused background will likely already have a grasp of these concepts. Still, it is a helpful refresher to inspire new ideas in even seasoned designers.

Structure

The book is broken in 6 parts with a total of 15 Chapters;

Chapter breakdown

- Part 1. A Focus on Understanding

- Chapter 1. From Information to Understanding

- Chapter 2. Understanding as a Function of the Brain, Body, and Environment

- Part 2. How We Understand by Associations

- Chapter 3. Understanding Is Fundamentally About Associations Between Concepts

- Chapter 4. Everyday Associations: Metaphors, Priming, Anchoring, and Narrative

- Chapter 5. Everyday Associations: Aesthetics and Explicit Visual Metaphors

- Chapter 6. Closing Thoughts and Cautionary Notes About Associations

- Part 3. How We Understand with External Representations

- Chapter 7. Why Our Sense of Vision Trumps All Others

- Chapter 8. An Intelligent Understanding of Color

- Chapter 9. Ways We Use Space to Hold and Convey Meaning

- Part 4. How We Understand Through Interactions

- Chapter 10. Interacting with Information

- Chapter 11. A Pattern Language for Talking About Interactions

- Part 5. Coordinating for Understanding

- Chapter 12. Seeing the System of Cognitive Resources

- Chapter 13. Coordinating a System of Resources

- Part 6. Tools and Technologies for Understanding

- Chapter 14. A Critical Look at Tools and Technologies for Understanding

- Chapter 15. A Perspective on Future Tools and Technologies for Understanding

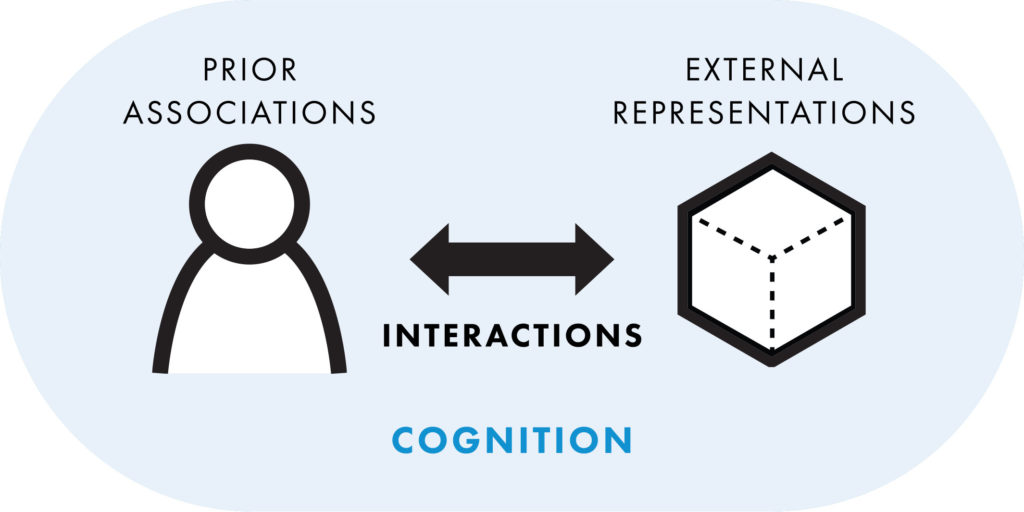

Part 1 focuses on where cognition happens. Parts 2 through 4 focus on how we understand – through associations, external representations and interactions. Then, part 5 describes systems of understanding in small and large groups, and part 6 looks at current, and possible future, tools that help us understand information.

Key Takeaways

From this book, you’ll learn about the ways we humans think and how we understand.

There are several different ways that we ‘make knowledge’, and these are often intertwined. Information is a resource, not a finished product, and needs to be transformed to aid understanding. I’ve summarised the book in 5 key takeaways and represented them in a sketch note.

1. Information does not equal understanding

For complex situations where there aren’t simple answers, Anderson & Fast remind us that understanding requires more than just access to information. We are only doing half of our job when we put the onus back on the user to make sense of information.

We are only doing half of our job when we put the onus back on the user to make sense of information.

2. Knowledge is influenced by prior associations

Prior associations impact how individuals interpret information, and these interpretations differ between people. Anderson & Fast explain that we ‘know’ things based on associations activated in our minds; we make sense of new information by linking it to a familiar concept.

Prior associations also come from narratives; we learn through stories (including fictional ones) and transfer meaning from them when we come across new information. In Chapter 3, the authors take a “short dystopian journey” (p.50) to a future where we have “permanent, updatable implants” in our brains that allow corporations and governments to “peer into our minds and access our most intimate thoughts”. The use of implants is the focus of my own PhD dissertation, and a large part of the misperceptions and fear that surround the topic are based on fictional claims such as these. Given the book emphasises how we use stories to make associations and learn, I think it is pertinent to remind a reader that this is a speculative future.

We also understand by identifying patterns; our minds are good at seeing patterns which are influenced by prior associations. What we see is based on what we already know. Meaning comes from associations whether they are intended or not.

The lesson that designers can take away from Anderson & Fast’s explanation of how associations influence thinking is that we need to carefully choose frames, words and visuals to ensure we are not invoking the wrong association that could result in misperception.

We need to carefully choose frames, words and visuals to ensure we are not invoking the wrong association that could result in misperception.

3. Knowledge influences external representations

We create external representations as a way to extend our thinking into the world using tools, models, drawings and more. This is an integral part of sense-making, not just a means of presenting information.

The authors explain how representations help create meaning by extending our thinking into the external environment. Visual representations make abstract ideas concrete by holding information. The way that information is arranged in space aids memory and recall, influences understanding, and conveys meaning. The arrangement (grouping, sequencing, ordering etc.) exposes abstract relationships between information. Presenting the same exact information in different ways (called isomorphic representation) can provide different perspectives in understanding and interpreting information.

4. Understanding is not simply ‘brain bound’

Thinking is not just confined to the brain – it’s spread across the body and the world. We extend our minds, and memory, by offsetting information into the external world. Our ability to understand is limited when we have to do all of the work in our heads.

Anderson & Fast explain that by representing information outside of our minds we can manipulate the information – allowing for new meaning to be created. Doing the thinking in the world rather than in our heads can be faster and more accurate. Furthermore, bringing thinking into the physical (or digital) world can be easier than imagining inside our heads. Another reason this is easier is because not everyone has the ability to do mental visualisation.

Doing the thinking ‘in the world‘ rather than ‘in our heads’ can be faster and more accurate.

5. Information is a resource to be interacted with

Anderson & Fast describe interaction as a part of the thinking process, not just a way to view information. It’s necessary to create understanding because interaction helps us see things in a new light. We make meaning by doing. When we manipulate information (physically or digitally) we make new connections which change our perception, therefore allowing us to see new meaning. It’s like how arranging scrabble tiles helps us see more potential combinations than with thinking alone.

Information itself is like pieces of a puzzle. It needs to be transformed, (the pieces put together) so we can understand what it means. We synthesise and transform information so that we can understand it. This book will teach you a myriad of ways that we think; by sorting, chunking, annotating and a myriad of other ways you will learn in this book. Specifically, Anderson & Fast teach readers 15 interactions used to understand information (grouped into 4 themes: foraging, turning, externalising and construction).

For designers, this means we should arrange information as an external representation in order to support perception and create understanding. We should also consider how we can allow users to perform these manipulations themselves to create understanding.

The Review

The good

- This book is educational. If you have your expectations set correctly up front (that it is not a ‘how-to’ guide) this book can give you new perspectives to bring to your work.

- It covers a breadth of topics. The book goes wide with the theory, covering many aspects with one book – from cognition to Gestalt principles.

- There’s still a lot of ‘figuring out’ to do yourself, but the examples throughout the book will likely spur your own thinking in how you can apply these concepts to your own work.

The ‘it depends’

- It’s theory informed. This can be both good and bad depending on your personal preference. Personally, I’m a big geek so I liked this. It may help you understand the why behind some things you are already doing as a designer and help you explain the theory to the business to get buy in.

- It’s cognitive science heavy. Similarly, this could be good or bad depending on your personal preferences (for me, it’s good). The authors spend a considerable amount of time explaining theories of mind, but then tell us that how the mind really works doesn’t matter for our purpose – and then go back to exploring cognition and where thinking happens. Confusing?

The bad

- Some of the theory feels repetitive. If you have read Daniel Kahneman’s ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’ any time in recent memory, many of the examples around perception and biases will be familiar and feel repetitive to you.

- The authors are good at pointing out that some examples are for Western cultures, but for other examples accessibility and diversity appears to be an afterthought. Vision is mentioned as powerful and important with little attention paid to blind or low vision individuals (although colour blindness, sign language and braille are mentioned briefly). The book also assumes that everyone can visualise in their mind, forgetting people with aphantasia. I raise this to remind you of other aspects we need to keep in mind when thinking about how people understand.

- Better proof-reading and copy editing was required. I make this comment based on three factors:

- First, issues with referencing, there are direct quotes without proper attribution (e.g. p.71). I’m not accusing the authors of plagiarism, but this is an annoyance for the reader. Another is that the referencing style changes throughout. This seems like a glaring oversight for a theory-heavy book about understanding.

- Secondly, some examples took me out of the narrative as I spent time trying to find answers that were either not included or involved flipping pages searching for answers. If you’re anything like me, and can’t leave things unsolved, this will lead you down a rabbit hole. Information that is difficult to navigate is ironic in a book about understanding!

- Finally, not all acronyms or models are explained in detail.

The TL;DR

‘Figure it Out: Getting from Information to Understanding’ leaves a lot for the reader to figure out themselves. But if you enjoy a theory-heavy volume (I know I do) there is a lot to learn from Anderson & Fast’s book.

Overall, I found it useful and it sparked some ideas for my own work. I took notes for my thesis dissertation, scribbled some diagrams for work, and discussed the concepts with a colleague. However, it is worth noting that the onus is on the reader to figure out exactly how to apply the theories and knowledge learnt, in order to then create understanding for our users.