If you’ve done any UX work at all, you’ve probably worked with and created personas.

Personas are fictional, archetypal characters that represent the users of a site or product. Personas can be very useful: they can help us see a design from new perspectives, make decisions, and uncover blind spots.

Sometimes, personas are based on existing user behaviour and your own research. They can also be invented fictions, intended to model the different kinds of users for a completely new design—something for which there aren’t any users yet, and so no existing behaviour to model.

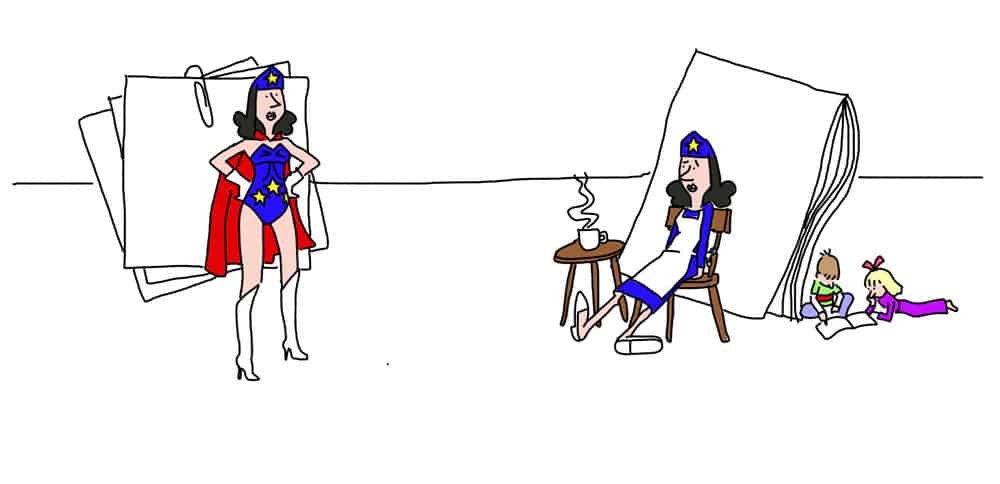

Either way, there’s often a blind spot built into the personas: they’re too perfect. I don’t mean that they’re too well made, but that the characterisation is usually sanitised, representing an idealised state of being.

The mid-30s stay-at-home mother personas never have troubled marriages, difficulty with their kids, or worries about ageing parents—unless those problems are directly relevant to the thing being designed. For a medical-information design, sure, the personas all have medical worries. But the personas for an online retailer almost never do.

Your instinct may be to reject such things as irrelevant. But think about it: our actual users, the ones for whom we’re trying to design these experiences, do have stresses and worries in their lives. After all, they’re human. And those stresses and worries, being part of them, are also a part of their interaction with everything in their lives. If that includes your design, then they will interact and react within the complete context of their messy, human lives.

When our personas fail to include stresses and worries that have little or nothing to do with whatever we’re creating, we’re actually blinding ourselves.

The bright smiles of a thousand cheery stock photos distract us, and the narrowly focused descriptions lead us astray. We’re more likely to think of our personas, and thus our users, as behavioural puzzles to be solved rather than as complete humans.

So as you write your personas and scenarios, don’t drain the life from them: be raw. Bring in snippets of users’ anecdotes if you have them, and include emotion wherever you can. Whoever picks these personas up down the line should feel as compelled to help them as you do.

When reading Susan’s profile I couldn’t help thinking that if she has free time to volunteer, why doesn’t she get a part time job instead? That would then help to solve the financial problems which would then help her marriage.

That is 1 problem of over detailed personas, the detail can be distracting.

Volunteering can satisfy a very different part of a person’s life than financial or relationship issues, and humans can be messy and internally inconsistent. This is the point Eric is making. We should include these details to challenge the way we problem solve as designers, developing empathy without judging.

Luke said it better than I could, really. Life is full of distracting details, and when we try to pare them all away and pretend that our users are simple stories, we mislead ourselves.

And honestly, I think having those kinds of apparent inconsistencies are even more valuable. You’re right, Reveley—if Susan got a part-time job rather than volunteer, that would ease the strains. So: what reasons might she have not to do so? Maybe she lives in an area where jobs are scarce. Maybe she has personal reasons not to take up a job, such as religious convictions or (as Luke said) valuing service over earning. Maybe she did have a part-time job in the past but kept having to take time off to deal with issues surrounding her autistic child, and eventually quit or was fired.

Those are just three fairly off-the-cuff examples. There are probably many more. But the thing that’s important, when we identify apparent inconsistencies, is to ask ourselves: what might explain this? It’s a moment for even deeper thought.

Not to diminish the strong point made by the article but I’m curious whether a humans ability to compartmentalize actions and behaviors slightly negates the need to add the archetypes imperfections?

Maybe not as all actions and reactions are related but I wonder if the author considered the neurology behind decision making? Is there any studies or evidence to help support this position?

p.s. I forgot to add the .com and the site pushed the error/notification to another page which then prompted me to hit the back button.