Since being launched in 2009 as a luxury car rental, Uber has redefined on-demand mobility and now operates in over 10,000 cities worldwide. Netflix, conceived in 1997 as a rent-by-mail DVD service, now streams in over 190 countries. And Airbnb, a bed and breakfast service that started in 2007, is now the largest accommodation provider with a global presence in over 220 countries.

In an economy where the average company finds it tough to not only grow but also sustain, it is worth considering how these brands have observed meteoric rise just within decades.

Besides good business sense and the funding to support expansion, it can be argued that all these brands had a strong focus on localization. For instance, Uber offers localization of services – UberCOPTER in the French Riviera, UberBOAT in Istanbul, and UberAUTO in India. It also launched UberENGLISH, a service designed to book drivers with English language familiarity in non-English speaking nations. Netflix offers localization of content – an extensive library of regional and country-specific content and high-quality dubbed versions and subtitles for international audiences. Airbnb realized early on that log-in preferences vary by region; today, it supports log-in via Google account, Facebook account, and email in the United States, while it provides Weibo and WeChat log-in in China. Yet, their localization strategies go deeper, reflecting a deep cultural understanding and sensitivity across their messaging, branding, and even advertisements.

Such localization that addresses the unique preferences of regional users is perhaps the ultimate hallmark of a global brand.

Why Should You Design for Different Cultures?

The way that certain messages, colors, and images are perceived by a cultural group may differ from the perceptions of another. So, as a brand, how you are viewed in a community will depend on your understanding of their culture and how you mold your messaging to be culture-specific. Communities can also demonstrate unique preferences for both tangible and intangible elements of design that are specific to their socio-cultural and religious identities, histories, and even political leanings. Many of these preferences may exist at a subconscious level, often as a product of unique mental models, decision-making processes, education, or even technological competence. Only by understanding cultures and the way they influence mental programming can brands create a relationship of trust and successfully compete against indigenous brands.

Brands that did not understand or failed to adapt to local preferences have historically struggled to sustain. For instance, eBay, which saw enormous success in the US – struggled to get a foothold in the Chinese market. It is suggested that eBay may have failed to support swift guanxi among Chinese users through instant messaging or other technologies, therefore preventing buyers from interacting with sellers. Such buyer-seller interactions, which are considered crucial for making purchasing decisions, were never encouraged, therefore leading to an erosion of trust.

When Should You Adapt Your Designs for Different Cultures?

Not every business needs to adapt its products for a cross-cultural audience. You may have limited cultural disparity between your target and local audiences, in which case, you do not require cross-cultural adaptation. Or, there may exist cultural differences, but these may not be large enough to warrant localization. In this case, you may offer language options in the product interface and website or provide instruction/product manuals in different languages.

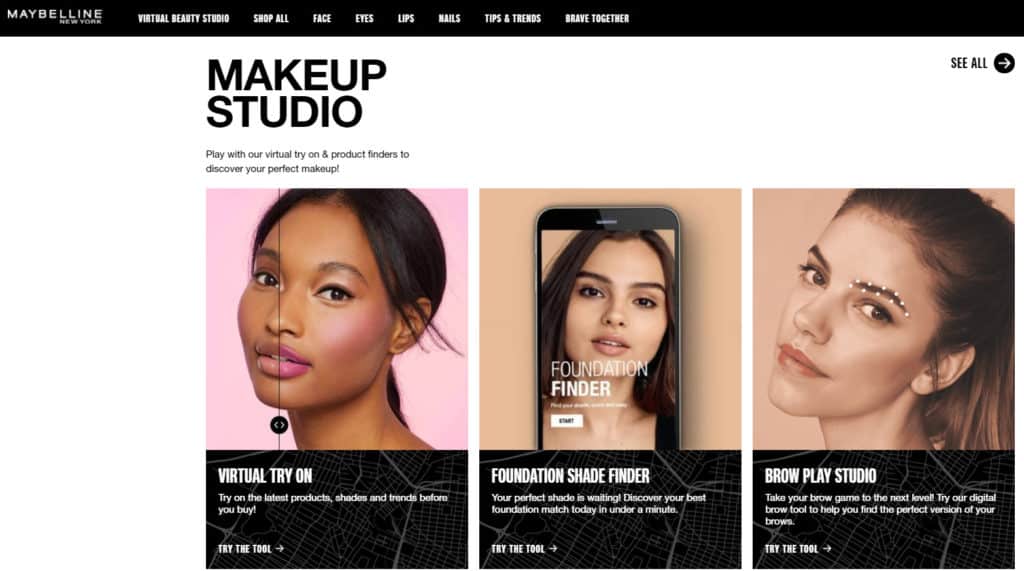

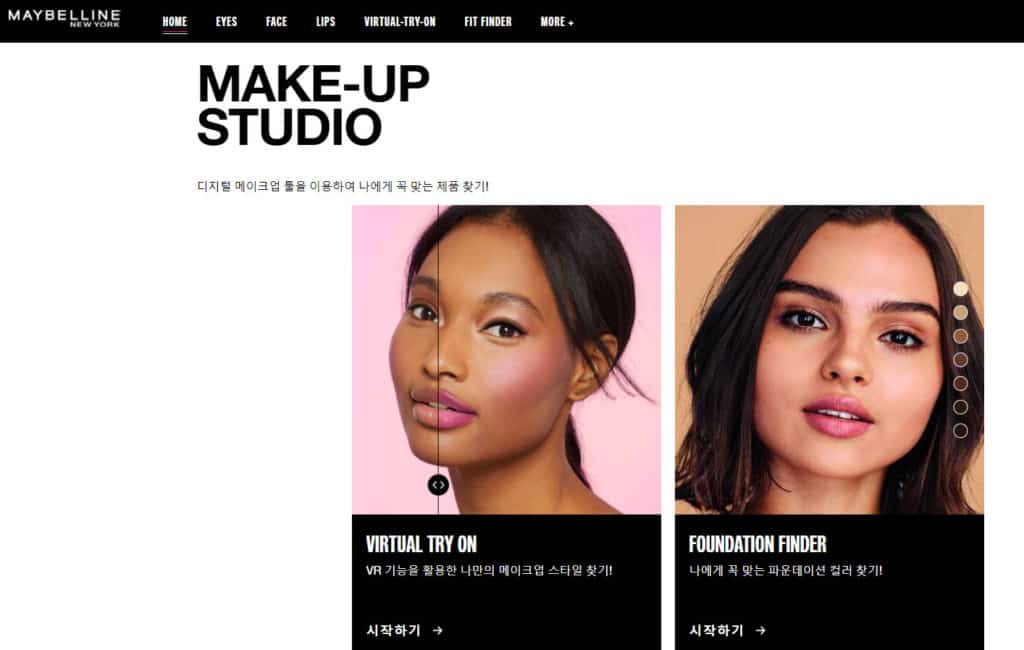

For example, the Maybelline website for South Korea has similar visuals and products to its US counterpart but offers translation in Korean.

If, however, one (or more) of these target groups are a sizeable percentage of your overall audience, you need to offer a localized, culturally-specific product(s) and interface(s). It means that you should translate your content, change currencies, offer preferred sign-in methods, and adapt visuals and metaphors so that the product feels locally produced.

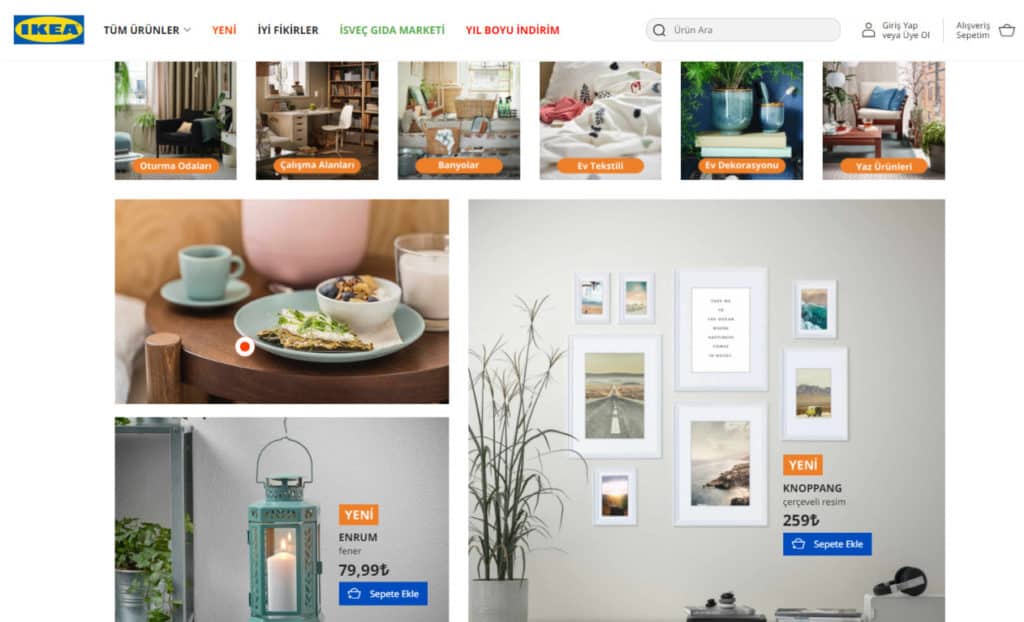

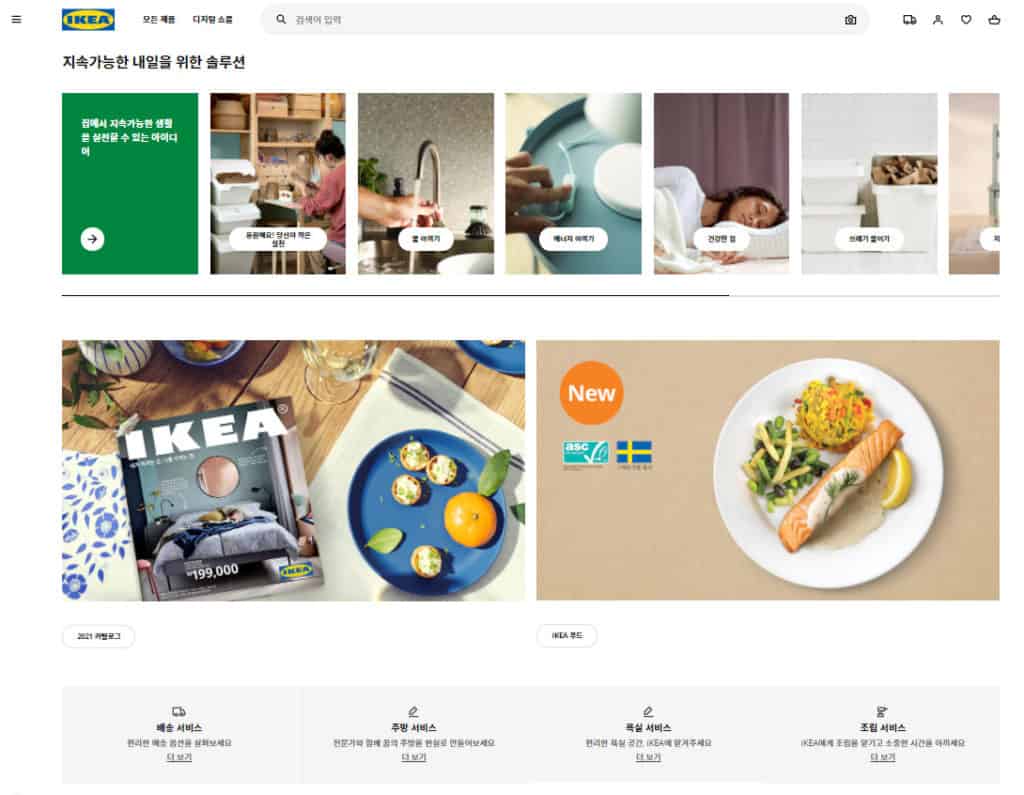

For instance, the IKEA websites for Turkey and South Korea differ in their product showcase, languages, and imageries.

Understanding Cross-Cultural Differences

To adapt your designs for a cultural group, you must first understand the cultural differences between your local and target audience. Understanding these differences would help you to determine to what degree your designs require adaptation.

Here are a few models that underline the differences among cultures.

1. Hofstede’s Cultural-Dimensions Theory

Perhaps one of the most comprehensive frameworks for assessing cultural differences was proposed by Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede. This framework defines six dimensions that outline a culture’s mental programming.

- Power distance index: The index quantifies how social inequality is perceived and accepted by those on the lower end of a power spectrum. According to Hofstede, high power distance cultures accept hierarchical orders and authority whereas, low power distance cultures strive to equalize power imbalances and accept authority based on true expertise.

- Individualism vs. Collectivism: This dimension reflects the degree to which a society thinks from an “I” or “we” mentality. Individualist cultures are loosely-knit groups where individuals act in their interests and make their own decisions. In contrast, collectivist cultures are tight-knit groups that act in the interests of the collective and make decisions based on the opinions of others.

- Masculinity vs. Femininity: Masculine societies tend to demonstrate a preference for achievement, material success, and assertiveness. Alternatively, feminine cultures prioritize cooperation and collaboration, avoids conflict, and prefer a high quality of life.

- Uncertainty Avoidance: This dimension reflects the degree to which a society accepts new ideas or unorthodox behavior. Cultures with high uncertainty avoidance are resistant to change and prefer familiarity over unfamiliarity and practice over principles. Whereas in cultures with low uncertainty avoidance, individuals take more risks and are more willing to try something new.

- Long-term vs. Short-term Normative Orientation: This dimension measures the ease with which societies adopt change. Cultures with long-term orientation are pragmatic in their approach. They believe that traditions can be adapted as per context and time, and they take decisions for the long term. On the other hand, short-term orientation cultures live in the present, maintain social codes and traditions, and do not worry about the future.

- Indulgence vs. Restraint: This dimension measures the degree to which individuals curb their impulses and wants. While indulgent cultures are more willing to accept the uninhibited satisfaction of human needs, restrained cultures set diktats that prohibit the gratification of needs.

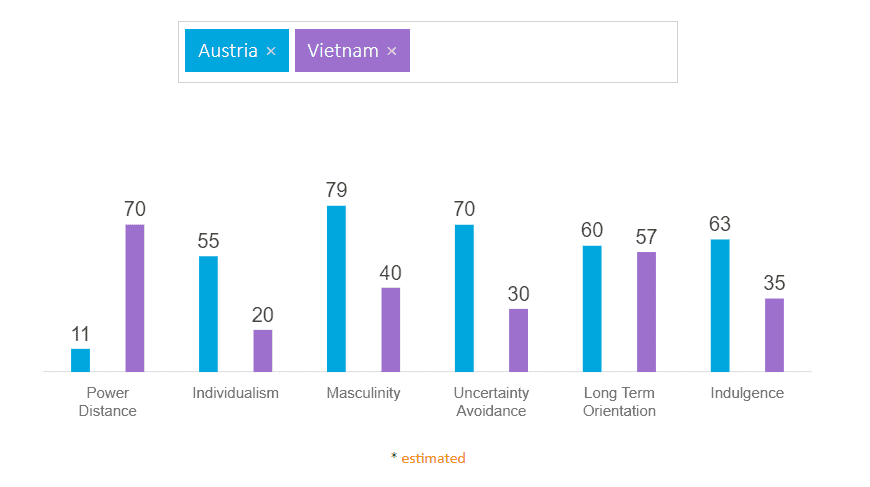

To see how different cultures differ on the six dimensions, you can use the country comparison tool. A comparison between the two nations – Austria and Vietnam – on Hofstede’s scale is shown below.

If your domestic audience is based in Austria, and you want to provide localized content for the target audience in Vietnam, then, based on Hofstede’s model of cultural dimensions, you must adapt your interface for higher power distance, collectivism, femininity, low uncertainty avoidance, and restraint. The reverse is true if your domestic audience is based in Vietnam.

2. Hall’s Cultural Context Model

Proposed by the American anthropologist Edward T. Hall, the cultural context model examines the relative importance of context in communication for different cultural groups. Low context cultures prefer information that is direct, explicit, and without ambiguity. This is because such cultures are more individualistic, and there is little expectation to understand each other’s histories and experiences. In contrast, high context cultures are collectivist societies with a preference for community harmony over individual achievement. In such cultures, communication is more subtle and context-driven, and emphasis is placed on the understanding of non-verbal relational cues.

While there are several other models for understanding cultural differences, it is important to understand that cultural models only suggest areas of inquiry to understand the current differences among populations. Cultural characteristics are fluid, and therefore the observations made in the past will hardly be relevant to modern audiences. So, instead of making stereotypical conclusions based on primitive observations, it is advisable to engage in active user profiling and research.

Adapting Designs Based on Cultural Differences

Assuming that the understanding of cultural differences is current and based on research, it is now possible to adapt designs based on an understanding of how communication, colors, symbols, and designs will be perceived by the target audience. To do this, we will compare two university websites, one from Austria and the other from Vietnam, and observe how cultural differences are manifest through design.

1. High Power Distance vs. Low Power Distance

For high power distance cultures, interfaces should be designed for easy navigation and quick information access. Applying religious and nationalistic themes, demonstrating expertise, and using figures of social or national importance can help engage such audiences.

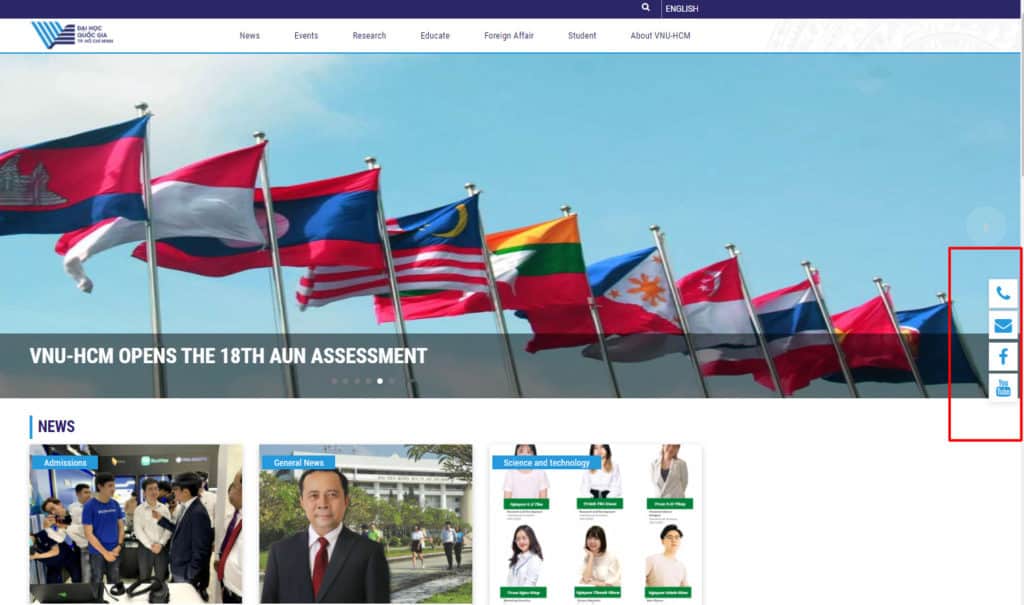

For instance, on the official website for Vietnam National University, the university ranking in the World University Rankings is given precedence over everything else. It is aimed to relay a sense of authority and earn the visitor’s trust.

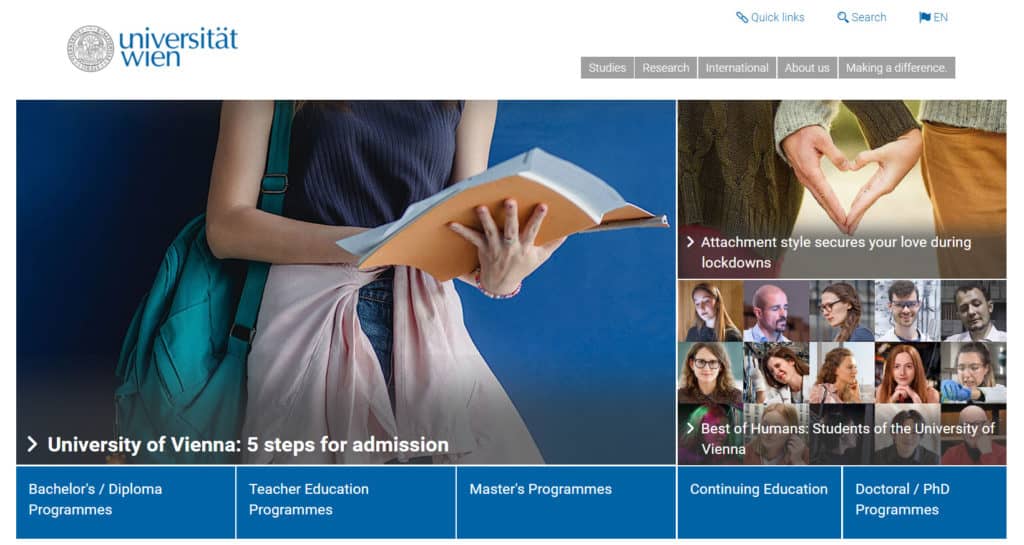

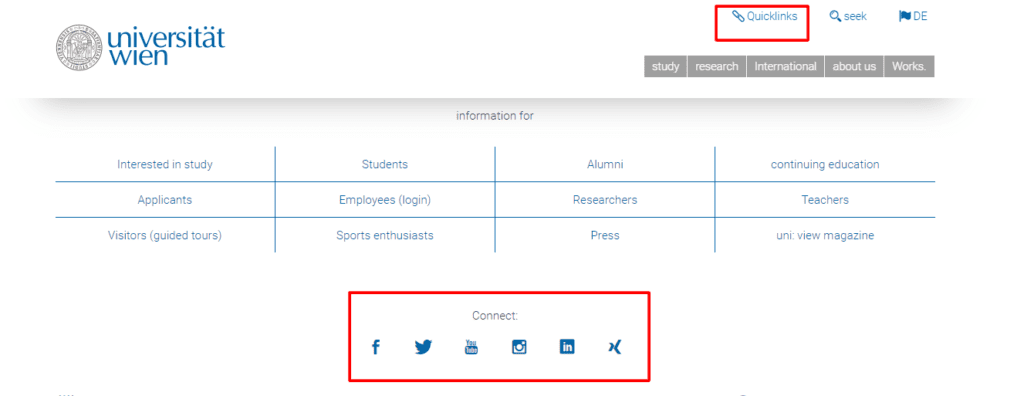

For low power distance cultures, informal organizational structures with visual elements that are universal or of popular appeal are favored. Communication must be informal but direct. For example, on the official website for the University of Vienna, the images show students and their stories upfront, rather than relying on reputation or University rankings. It is noteworthy that Vietnam has a power distance of 70 against Austria’s 11 on Hofstede’s scale.

2. Individualism vs. Collectivism

When designing for individualistic cultures, information on how the product or service benefits individuals or helps them succeed must be delivered. Themes signifying achievement, youth, vitality, and materialism can be utilized.

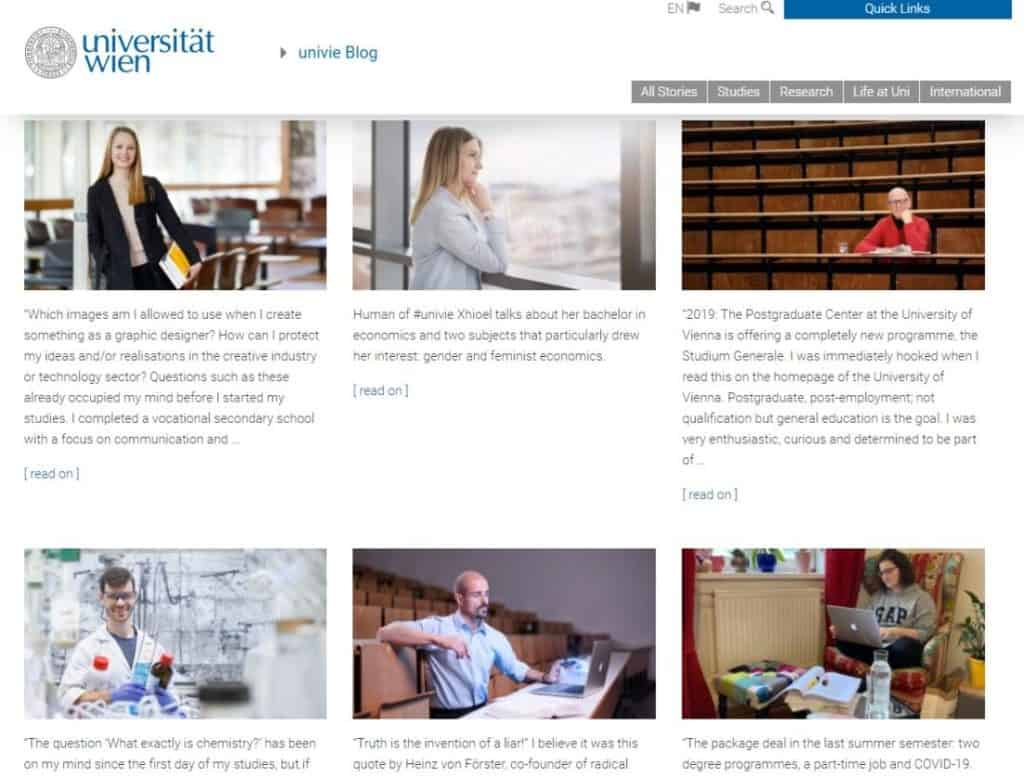

The University of Vienna site has a dedicated blog called “Humans of University of Vienna,” focused on student stories and achievements. Almost all these stories focus on the individual rather than the team.

For collectivist societies, information that reflects how the product or service benefits the cultural group must be delivered. Themes surrounding community harmony and peace and visuals focused on history and tradition work well with such audiences. It is best to provide feedback elements, such as social media sharing options, reviews, or “popular” categories, to help them with their decision-making.

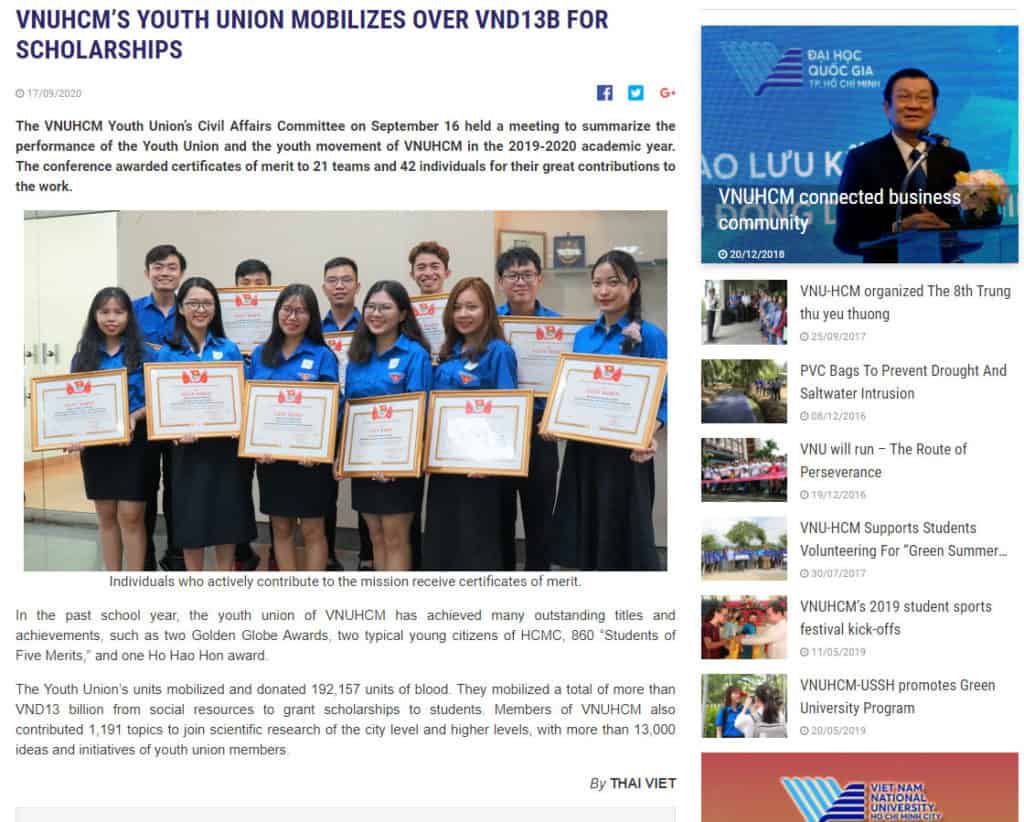

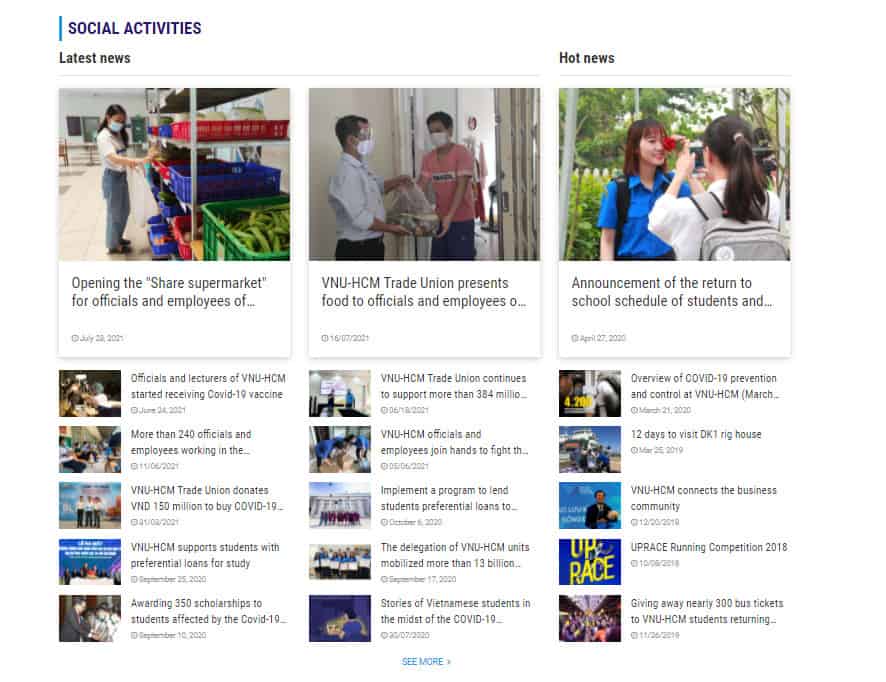

There is a strong focus on team achievements throughout the website for Vietnam National University, as shown in the image below.

3. Masculinity vs. Femininity

Interface designs for masculine societies should be of high functionality, allowing exploration and easy control while driving the quick realization of goals. The content must make a clear distinction between age groups and genders. Incentives and reward systems can be employed to grab interest.

Austria scores higher on the masculinity index than Vietnam. Note how the University content is categorized so that visitors get what they are looking for without exploring the whole website.

Interfaces designed for feminine cultures need to be engaging, offer positive experiences through visual aesthetics, and support collaboration and exchange of ideas. It is vital that such interfaces are gender-neutral and designed to suggest a blurring of gender roles.

The Vietnam National University website allows visitors to leave comments and feedback across different pages, as in the image below. This was not observed for the University of Vienna website.

4. High Uncertainty Avoidance vs. Low Uncertainty Avoidance

Interfaces aimed at high uncertainty avoidant cultures must look official and professional. They must offer simple navigation, prevent users from getting lost, and avoid user errors. Such interfaces must provide limited menu options and provide information in a simple structured way without ambiguity. Content must be language and culture-specific to drive familiarity, while visuals and colors that reinforce the messaging must be applied.

Austria scores higher on uncertainty avoidance compared to Vietnam. The Austrian website offers an organized footer with helpful links and a sitemap to prevent visitors from getting lost. On clicking, the different sections are further segregated to provide visitors with the information they seek.

Interfaces for low uncertainty avoidant audiences may be complex, offer several menu options, and support exploration. Designs and visuals may be more cutting-edge, and images and colors that drive meaning and interpretation may be applied.

The footer in the Vietnam National University website provides the main categories. The information in each section is less organized than in the University of Vienna example.

5. Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation

The interface for an audience with long-term orientation must support the presentation of relevant and detailed information with clear benefits and in a way that is convincing but unhurried. Content and visuals must serve the information sought. UI elements, such as wishlists and social media sharing options must be provided so that users can revisit the site.

For short-term orientation cultures, design the UX for a quick achievement of goals. Use shortcuts and clear CTAs to take immediate action. Avoid complex navigation and browsing and provide only relevant and useful images and links.

Austria and Vietnam are almost similar in their normative orientation scale. Both host prominent social media sharing options. The University of Vienna website also contains quick links and supports quick browsing, as evident in the earlier examples.

6. Indulgence vs. Restraint

When designing for an indulgent audience, you must offer more options and categories to choose from and purchase. Showing related items and offers and providing freebies are other ways to cater to such an audience.

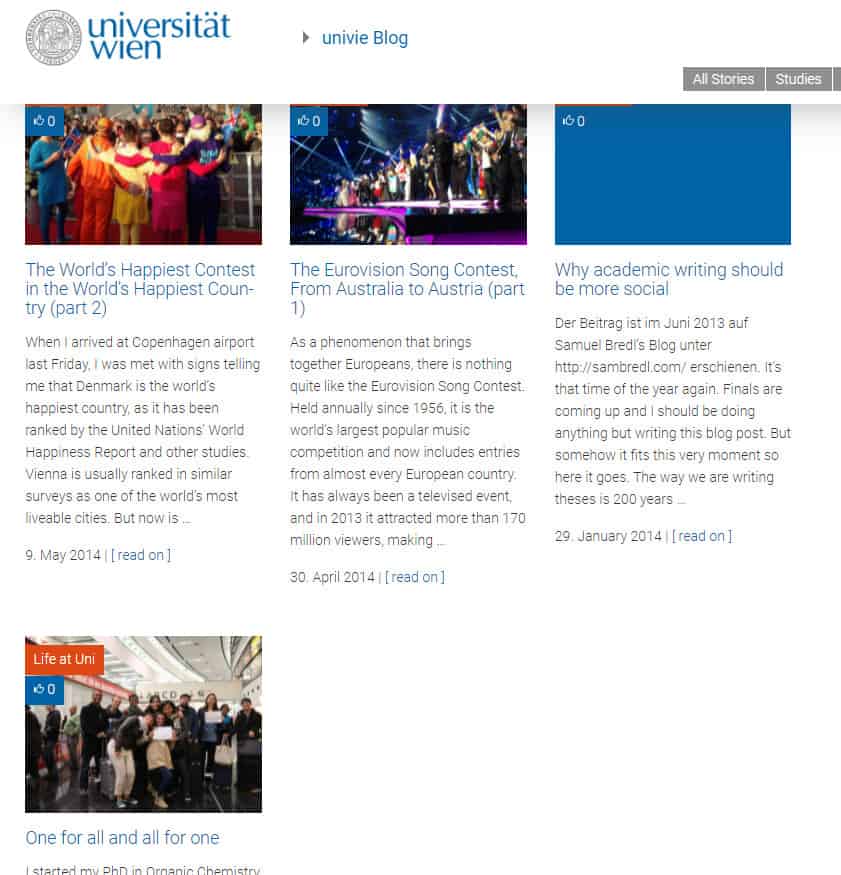

The images and content in the “Life at Uni” and “Humans of University of Vienna” convey a sense of casualness and fun that signify the autonomy of students.

For a restrained audience, it is advisable to limit the number of options and show ways to save money through discounts. Further, information on corporate social responsibility helps to engage such audiences.

Images and the tone and presentation of content on the Vietnam National University website conveyed seriousness and reserve. There was limited focus on the inner lives of students on campus.

7. High-Context vs. Low-Context

Interfaces for high-context cultures may have complex architectures with multiple sidebars and menus that encourage exploration. Heavy use of images and banners is also typical of such interfaces. Images that elicit emotions or highlight collectivist principles, such as featuring the use of products by other individuals, are used. Communication is polite and more nuanced.

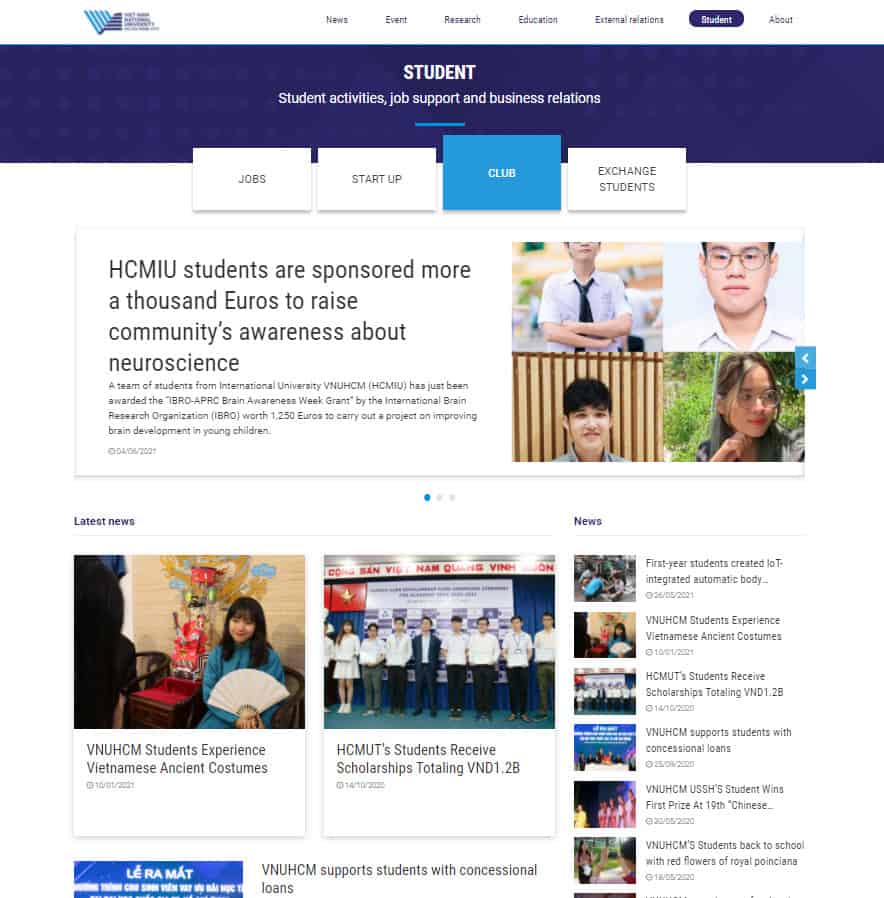

Since Vietnam scores higher than Austria in collectivism, we can assume that Vietnam is a high-context culture. The news page on the Vietnam National University website is prolific with images and banners. There is also an emphasis on social activities, community building, scholarships, and trade union news.

The principles of individualistic cultures guide the design of low-context culture interfaces. Navigation is simple with limited menu and sidebar options, and images and links are fewer. Communication is explicit and precise, and images that signify personal accomplishment are used.

Since Austria scores high on individualism relative to Vietnam, it should have a low-context culture. The news page for the University of Vienna website is far simpler than the Vietnamese website, with fewer banners, images, and categories. There is a greater focus on scientific content than community news.

Understanding Limitations

While cultural models provide a framework for understanding cultures and making design adaptations, these are largely inadequate in addressing the cultural nuances of individuals and subgroups. This is because the boundaries of culture are impossible to confine within geographical or national borders. Many cultures and subcultures may exist in the same region with marked differences making such models reflective of averages at best—further, culture changes with time and over generations. The impact of factors outside the individual and the community, such as education, the use of technology, the political and legal frameworks, or interaction with other cultural groups, are also important parameters that would define the relationship of your target audience with technology or their perception of usability.

However, these models can offer psychological insights to inform the design process. The ideal strategy, therefore, is to apply the understanding of cultural differences as broad principles but drive cross-cultural UX with a true understanding of cultures derived through in-depth research and cultural immersion.

The Essential Design Elements That You Must Get Right

Charles Eames said,

“The details are not the details. They make the design.”

Nowhere is this truer than in cross-cultural design, for true localization lies in the details.

There are certain elements of design that you must nail to get localization right.

- You must get geopolitical details right, especially when using maps with disputed territories. In many religions, certain foods may be prohibited at specific times or around the year, while in others, norms around dressing may exist. The messaging and imageries used must be sensitive to all such cultural, religious, social, or geopolitical sentiments.

- Different cultures interpret colors differently and the significance associated with colors in one culture may differ significantly from another. To ensure effective localization, ensure that you adapt colors to suit the cultural sensibilities of your target audience.

- Like colors, symbols are also subject to culture-specific interpretations. When adapting your design for a cross-cultural audience, ensure that the symbols used are familiar and drives the right meaning.

- On translation, text lengths may change. To ensure minimal changes to the UI after translation, ensure ample padding for your design elements. Further, languages can have both horizontal and vertical alignment. While most languages with horizontal alignment read from left to right, others like Arabic and Persian read from right to left. For all such orientations, the correct placement of text, images, and CTAs should be ensured.

- Sometimes perfection lies in the detail. For instance, when designing a form, allow users the flexibility to insert special characters, or a wider space to type a longer name. You should also be mindful of the different formats for date and phone numbers, the metric systems used, and currency and conversions.

The Takeaway

In today’s globalized world, for a business to make its presence felt outside the home turf, it must form a relationship of trust with its audience. Design can be a powerful tool to build this trust, but it must be guided by an understanding of the audience and their cultural identities. Cultural models help suggest the mental maps of the target cultural group based on an analysis of cultural differences. However, culture models must only be used as principles to guide audience research, for it takes much more to design nuanced and inclusive UX that is not only respectful and empathetic but also usable. The latter can only be achieved with in-depth UX research and cultural immersion.

Dear Ananya, I enjoyed reading what you wrote

Hi Mehrnaz, really appreciate you saying that. I hope the article was of some value to you.

Interesting article