It’s a diverse world we live in. Around 13% of the population in both the US and the UK was born overseas, jumping to 25% of the population in Australia. Technology and online communication continue to make geographical separation less relevant.

But while geography may be less relevant in the digital age, culture hasn’t lost its significance. If you’re conducting usability testing in a cross-cultural setting, it’s important to be prepared. After all, in an ever-globalising world, chances are that cross-cultural usability testing will crop up at some point in your career.

I learnt about cross-cultural usability testing the hard way when I was working on a project which involved a significant Japanese audience. I had never been to Japan or had the opportunity to get to know their culture in-depth.

The first round of testing for my project didn’t go well, which was a surprise. I thought I had set clear expectations with the group about speaking thoughts aloud. The findings were confusing, and I didn’t get a good sense of mutual communication, despite good rapport and good participation.

I discovered afterwards that I had made a few assumptions that led me astray. I didn’t realise that Japanese people tend to communicate implicitly, or indirectly via signals like body language and facial expressions. A think-aloud method was a big leap from their usual communication style.

Once I realised this, I changed my program to better accommodate those cultural differences. This led to far better results in the sessions that followed.

Here are a few important lessons I picked up along the way, which will come in handy if you find yourself about to embark on cross-cultural usability research.

1. Establish rapport and trust from the beginning

When there’s an obvious cultural difference, it’s even more important to build trust early on. Pay more attention than usual to addressing concerns and questions of each participant at the outset.

2. Avoid stereotypes and assumptions

Assumptions can lead you astray in any usability testing scenario. In cross-cultural testing, it’s even more important to leave assumptions at the door and create a non-judgemental space.

Avoid stereotyping, which is easier to fall into when you’re floundering in new contexts. Suspend any judgements that aren’t specifically related to the research.

3. Be sensitive to cultural differences

Be mindful of cultural taboos, inappropriate topics and the way race, gender and class might affect things.

For example, while Americans wouldn’t bat an eyelid at pointing to someone, a Thai person would find this offensive, instead using their chin to indicate the person. Equally, there might be topics your group isn’t comfortable discussing.

4. Define the boundaries

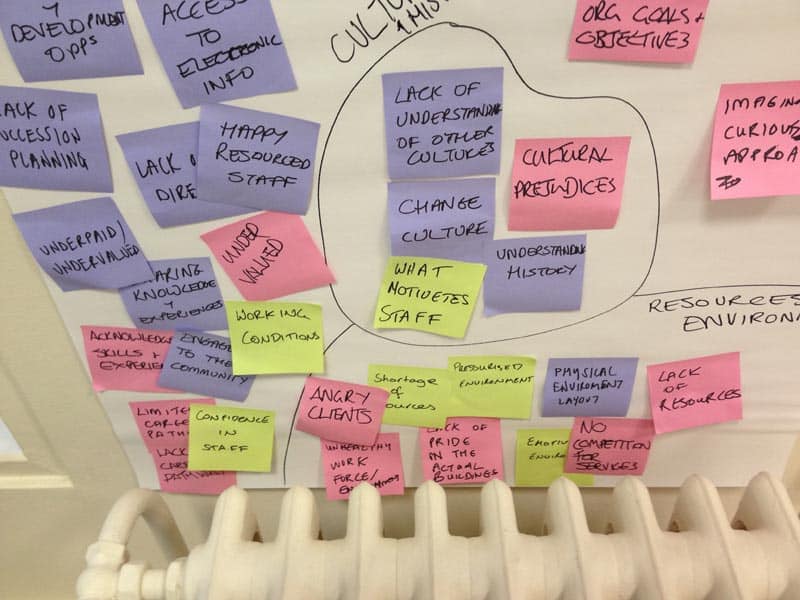

You can use a simple exercise to understand what people are happy to talk about. With my Japanese group, I created hand-drawn index cards with the interview topics written on them. We then played a sorting ‘game’ where they put them in two piles, of either ‘private’ or ‘public’ and had the ability to comment on their choices.

Any topics in the ‘private’ pile that I could live without, I discarded. The other ‘private’ ones I was very careful when asking amongst the other topics during the interview. I raised some others gently towards the end, after explaining why I needed to know, and only when I felt I had established a harmonious relationship with the participant.

5. Create cultural bridges

While understanding and acknowledging cultural differences is important, so is finding things you have in common.

I used a whiteboard to take turns playing another simple ‘game’ that acknowledged our different cultural backgrounds. We used this opportunity to figure out what we had in common, creating cultural ‘bridges’ throughout the session which helped establish rapport.

6. Be sensitive to language barriers

If language is an issue, make sure you communicate to participants as simply and clearly as you can.

Use straightforward language. Avoid metaphors, proverbs and colloquialisms, which are likely to confuse non-native English speakers. Be mindful that verbal and non-verbal cues are likely to be different.

Don’t forget to allow extra time. Most people might translate the English into their native language to understand better before responding.

7. Get a second set of eyes and ears

Given the increased potential for misreading signals or behaviour, the need to have a second person scribing notes is even more important than usual. A second perspective might help pick up things you miss.

A cross-cultural element in your usability testing adds an extra layer of complexity. But a little cultural sensitivity and preparation will go a long way to help you get meaningful results.

Do you have experience with cross-cultural usability testing? Share your tips in the comments.